The London and the South East Years

If you’ve plodded gamely through The Bournemouth Years and haven’t yet lost the will to live, you’ll be relieved to know that this section contains a bit less detail, (or at least it started out that way). That’s partly because I’ve reached the age when I can recall what happened fifty years ago but can’t remember where I left my reading glasses, and partly because most, though not the worst, of the embarrassing moments took place in those early years. Anyway, here we go…

If you’ve plodded gamely through The Bournemouth Years and haven’t yet lost the will to live, you’ll be relieved to know that this section contains a bit less detail, (or at least it started out that way). That’s partly because I’ve reached the age when I can recall what happened fifty years ago but can’t remember where I left my reading glasses, and partly because most, though not the worst, of the embarrassing moments took place in those early years. Anyway, here we go…

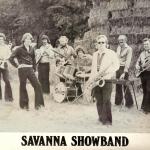

By 1977, living in Surrey and working in the City, I realised I wanted to get back into playing. Having made the decision, I suppose I half expected the phone to start ringing, as had usually happened in my Bournemouth days, but it sat there in silent defiance until I plucked up courage to approach Alan Swinden, a fellow parent at my children’s school, whom I’d discovered played bass in a band. The band specialised in Shadows numbers, which tend to make a piano player about as useful as a fifth wheel on a sledge, but soon after I joined we teamed up with a brass section led by Tommy Cooper‘s nephew, John, and became The Savanna Show Band.

John acted as agent, bandleader, and vocalist, and also handled trumpet. On top of that he had charm in abundance (the ladies in the audience loved him) and could read a room better than anyone else I’d then worked with. He could also think fast on his feet, as he proved when Graham, the tenor player, stormed off halfway through a New Year’s Eve gig, never to return, due to a row over a woman, thus leaving us as a seven-piece instead of the eight-piece that had been booked. “Keep moving around and they’ll never notice” said John. He was right, and Graham’s money for the night was shared out between the rest of us. (Incidentally Tommy Cooper turned up (late)at John’s wedding and the old cliche about him is absolutely true: he only had to walk into a room to put you into fits of laughter.) Some years later John ran a hugely successful big band in South Africa under the name of Jonny Cooper.

John acted as agent, bandleader, and vocalist, and also handled trumpet. On top of that he had charm in abundance (the ladies in the audience loved him) and could read a room better than anyone else I’d then worked with. He could also think fast on his feet, as he proved when Graham, the tenor player, stormed off halfway through a New Year’s Eve gig, never to return, due to a row over a woman, thus leaving us as a seven-piece instead of the eight-piece that had been booked. “Keep moving around and they’ll never notice” said John. He was right, and Graham’s money for the night was shared out between the rest of us. (Incidentally Tommy Cooper turned up (late)at John’s wedding and the old cliche about him is absolutely true: he only had to walk into a room to put you into fits of laughter.) Some years later John ran a hugely successful big band in South Africa under the name of Jonny Cooper.

In addition to the normal round of British Legion clubs, works canteens and private functions, John’s contacts through his agency soon started producing gigs at large and prestigious local venues, such as The Fulcrum, Slough and The Hexagon, Reading (where, if they’ve got a snooker championship the following day, the entire stage is lowered about six feet on hydraulic ramps, which can be a bit disorientating when you’re packing up your band gear with five pints of beer inside you).

As the gigs improved, so did our repertoire, helped by the fact that three new members – Dave Crabtree on sax, Barry Caws on lead trumpet, and Brian Kirby on guitar – could also handle lead vocals. That gave us a much greater range of potential material, and we gradually extended the sets to include anything from James Last to Stevie Wonder, which made a nice change from Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree and The Birdie Song. (Bet you don’t remember who did that one – it was The Tweets, described in the Guinness Book of British Hit Singles as “UK, male feathered vocal/instrumental group.”)

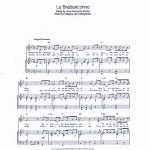

Where was I? Oh, yes, we were widening our repertoire. That’s generally a good thing, but one can go too far, as I did with the Belgian National Anthem. (NB. This incident may have taken place after we’d formed Tequila Sunrise – see next paragraph – but it’s a true story and this is as good a place as any to tell it.) We were booked to play at a function to celebrate, I think, a Berkshire town being twinned with a Belgian one, (presumably Rio or LA were already spoken for), and the Belgian Ambassador was due to attend. In such circumstances, their embassy sends you the music, complete with chord symbols, and, fortunately for me, a tape of the anthem – La Brabanconne. Now I don’t subscribe to the view that “Belgium is boring”, but, alas, La Brabanconne does tend to undermine my case. However, I dutifully applied myself to learning it parrot-fashion, and at the start of the gig managed to get through it without His Excellency ripping off his sash in temper. Thinking all was now well, I applied myself with my usual gusto to the numerous pints that helped to make our gigs go with a swing, until, to my horror, at the end of the evening, as the last notes of God Save the Queen died away, I heard the local Mayor ask the audience to “please remain standing for the Belgian National Anthem.” This presented me with two problems: (a) I’d lost the chord sheet supplied by the embassy and (b) I had absolutely no recollection of how the tune went. With sweat pouring off me, I launched desperately into the only sombre tune I could think of (I think it was the Masonic Grace, which does use some of the same notes, though not in the same order), and ploughed gamely on to the end. To his credit, the Ambassador managed to keep a straight face, and most of the British non-masons in the room probably never noticed the difference.

Where was I? Oh, yes, we were widening our repertoire. That’s generally a good thing, but one can go too far, as I did with the Belgian National Anthem. (NB. This incident may have taken place after we’d formed Tequila Sunrise – see next paragraph – but it’s a true story and this is as good a place as any to tell it.) We were booked to play at a function to celebrate, I think, a Berkshire town being twinned with a Belgian one, (presumably Rio or LA were already spoken for), and the Belgian Ambassador was due to attend. In such circumstances, their embassy sends you the music, complete with chord symbols, and, fortunately for me, a tape of the anthem – La Brabanconne. Now I don’t subscribe to the view that “Belgium is boring”, but, alas, La Brabanconne does tend to undermine my case. However, I dutifully applied myself to learning it parrot-fashion, and at the start of the gig managed to get through it without His Excellency ripping off his sash in temper. Thinking all was now well, I applied myself with my usual gusto to the numerous pints that helped to make our gigs go with a swing, until, to my horror, at the end of the evening, as the last notes of God Save the Queen died away, I heard the local Mayor ask the audience to “please remain standing for the Belgian National Anthem.” This presented me with two problems: (a) I’d lost the chord sheet supplied by the embassy and (b) I had absolutely no recollection of how the tune went. With sweat pouring off me, I launched desperately into the only sombre tune I could think of (I think it was the Masonic Grace, which does use some of the same notes, though not in the same order), and ploughed gamely on to the end. To his credit, the Ambassador managed to keep a straight face, and most of the British non-masons in the room probably never noticed the difference.

After three years we decided to part company with John Cooper,

and in 1980 became “Tequila Sunrise,” with Brian Kirby as bandleader, though I helped out in getting some of the gigs. (According to Alan Swinden I even tried to get a booking for the Berkshire Police Ball when we were stopped by a patrol car at 3.00 a.m. on the way back from a gig. My sales pitch didn’t work, but the traffic cop got bored and let us go on our way.) We managed to keep the connection with The Fulcrum, and a steady flow of work came in, often with us as the supporting act to “name” bands, such as Joe Loss, Victor Sylvester, Ray McVeigh etc. and headline acts such as Barbara Dickson, whose Scottish road crew insisted on pelting us with ice cream tubs from the wings, after they’d had a few bevvies too many. We’d by now added a super female vocalist to the lineup and always managed to hold our own against the headline bands, largely by switching the balance of our sets away from waltzes and quicksteps, which they could obviously play better than us, towards more pop-orientated material, and were starting to get a bit cocky about it. Then one New Year’s Eve we found ourselves supporting the Sid Lawrence Orchestra.

Spike Milligan once said “Sid Lawrence is the name of the German pilot who shot down Glenn Miller so he could steal all his arrangements.” Wherever Sid got them from, the resemblance to the Miller sound was uncanny, and everyone who turned up at The Fulcrum that night came expecting just that. I suppose the first inkling we had that this wasn’t going to be yet another successful support gig, came when we saw the size of the band. There seemed to be hundreds of them, and even though we’d set up in a corner of The Fulcrum’s vast stage, they still had to wrap themselves around us. Our first set came to an end, still with a largely empty dance floor, and then it was time for me to step up to the microphone and say, “Ladies and Gentlemen, will you please welcome Mr. Sid Lawrence.” As, all around me, the orchestra struck up their sustained opening chord, it felt like I was going down in a lift. Our second set went down no better than the first one, even though we played well, and we saw in the New Year in a somewhat restrained mood.

At least, however, we actually had an audience, albeit not interested in us, that New Year’s Eve, but it wasn’t always so, at least up to a point. We’d been booked to play at a hotel somewhere near, I think, Dunstable. It was a ticket-only do, and the money was good, and if we did okay there was the chance of repeat gigs. The first hint that the evening might turn out to be somewhat short of a roaring success came when we spotted a hoarding advertising a free gala dance to celebrate the opening of a new leisure centre just down the road from the hotel. We thought no more about it, however, as we busied ourselves setting up the band gear and rope lights, and then chucked down a few pints as we prepared ourselves mentally for the usual influx of hordes of punters. With the tape deck playing in the background, (we took a less than evangelical approach to the Musicians’ Union slogan of “Keep Music Live”), our unease grew as our start time of eight o’clock came and went, with no sign of an audience. By twenty past eight, two middle-aged couples had arrived separately and were clearly going through the first stages of denial that they had made a grievous error in paying for their tickets in advance. They were also drinking quite fast.

At least, however, we actually had an audience, albeit not interested in us, that New Year’s Eve, but it wasn’t always so, at least up to a point. We’d been booked to play at a hotel somewhere near, I think, Dunstable. It was a ticket-only do, and the money was good, and if we did okay there was the chance of repeat gigs. The first hint that the evening might turn out to be somewhat short of a roaring success came when we spotted a hoarding advertising a free gala dance to celebrate the opening of a new leisure centre just down the road from the hotel. We thought no more about it, however, as we busied ourselves setting up the band gear and rope lights, and then chucked down a few pints as we prepared ourselves mentally for the usual influx of hordes of punters. With the tape deck playing in the background, (we took a less than evangelical approach to the Musicians’ Union slogan of “Keep Music Live”), our unease grew as our start time of eight o’clock came and went, with no sign of an audience. By twenty past eight, two middle-aged couples had arrived separately and were clearly going through the first stages of denial that they had made a grievous error in paying for their tickets in advance. They were also drinking quite fast.

By half past eight it was crunch time. No one else had turned up and, if we wanted to get paid, we had to get on with the first set. We launched bravely into “American Patrol”, the sound reverberating round the virtually empty room, and segued into “Greensleeves”. Neither couple got up to dance the quickstep, but the braver (or maybe drunker) pair did finally attempt a waltz, and the remaining couple felt obliged to follow. It was becoming increasingly apparent, however, that our audience of four were soon going to up sticks and leave us with an empty ballroom, giving us the choice of playing to no-one at all, or packing up and risking not getting paid. “Why don’t you talk to them?” eventually whispered the bass player, Tony Eden, in my ear. I could see the psychology of that – find out their names, get to know them, and pretty soon we’d be holding them hostage – each couple feeling too guilty to be the first to walk out on us. And finally, Stockholm Syndrome would kick in, and they’d come to love and admire their captors, and have a really nice evening.

I wish I could tell you that that’s what happened, and they came to know each other, and are to this day still going on caravan holidays together. The truth, alas, is more mundane. With a bit of chatting to them, we did manage to keep them there long enough to justify our getting paid, but they finally left within a few minutes of each other. They probably went on to the free gala dance down the road.

By the mid 1980s, the sax player, Dave, and I had decided we wanted to turn our hand to jazz. We’d had some great times with Tequila Sunrise (for me, the most memorable was playing solo piano for Matt Monro singing “Birth of the Blues”), but it was time to move on, and we left, followed soon after by Mick, the drummer, to form a jazz quartet, with Chris Robin on bass. Dave had by far the best jazz technique, but we all gradually began to improve, and a few pub gigs started coming in. It was when Peter Giles, (see The Bournemouth Years), took over on bass that the band – now known as Birdland, and which features on tracks 4, 6 and 9 of my Pure and Simple album and tracks 4, 8 and 11 of And Another Thing… – started moving ahead.

By the mid 1980s, the sax player, Dave, and I had decided we wanted to turn our hand to jazz. We’d had some great times with Tequila Sunrise (for me, the most memorable was playing solo piano for Matt Monro singing “Birth of the Blues”), but it was time to move on, and we left, followed soon after by Mick, the drummer, to form a jazz quartet, with Chris Robin on bass. Dave had by far the best jazz technique, but we all gradually began to improve, and a few pub gigs started coming in. It was when Peter Giles, (see The Bournemouth Years), took over on bass that the band – now known as Birdland, and which features on tracks 4, 6 and 9 of my Pure and Simple album and tracks 4, 8 and 11 of And Another Thing… – started moving ahead.

We knew the Count Basie Orchestra was in town and decided he must be one of Basie’s sidemen, and would probably consider our playing pathetic. Fortunately he turned out to be Karl, the doorman, and the gig turned out fine, and over the years we were lucky enough to have some fine musicians sitting in with us, including Jean Toussaint from Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers (see image on right). Palookaville was a very trendy venue for some years and we often had out fair share of celebs in the audience, including Richard Littlejohn, the Daily Mail columnist and broadcaster, and on one occasion a group of ballerinas dancing in front of the stage, fresh from performing at the Royal Opera House around the corner. These included a young Darcy Bussell, then a principal ballerina with the Royal Ballet. For a video of Birdland playing at Palookaville please click on the YouTube button in the top right-hand corner of this page.

We knew the Count Basie Orchestra was in town and decided he must be one of Basie’s sidemen, and would probably consider our playing pathetic. Fortunately he turned out to be Karl, the doorman, and the gig turned out fine, and over the years we were lucky enough to have some fine musicians sitting in with us, including Jean Toussaint from Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers (see image on right). Palookaville was a very trendy venue for some years and we often had out fair share of celebs in the audience, including Richard Littlejohn, the Daily Mail columnist and broadcaster, and on one occasion a group of ballerinas dancing in front of the stage, fresh from performing at the Royal Opera House around the corner. These included a young Darcy Bussell, then a principal ballerina with the Royal Ballet. For a video of Birdland playing at Palookaville please click on the YouTube button in the top right-hand corner of this page.

We ended up playing at Palookaville for more than ten years, supplemented for a year or two by The Brahms and Liszt round the corner in Russell Street, and by a steady flow of functions. The most prestigious of these found us in the BBC Governor’s Council Room at Broadcasting House, surrounded by Epstein busts, playing to an audience which included several members of the then Conservative cabinet and their shadow counterparts. (I remember a young John (now Lord) Prescott, a noted jazz fan, paying almost as much attention to us as he was to an even younger Diane Abbott). I’m told that no other band has played in that inner sanctum, either before or since.

Palookaville finally closed when the lease was up, and the premises became a clothes shop. With the disappearance of our main source of gigs, Les Booth, who’d replaced Pete on bass, and Dave went their separate ways, and Mick and I teamed up with Tony Eden to do rock’n roll pub gigs under the name of Bus Pass.

Palookaville finally closed when the lease was up, and the premises became a clothes shop. With the disappearance of our main source of gigs, Les Booth, who’d replaced Pete on bass, and Dave went their separate ways, and Mick and I teamed up with Tony Eden to do rock’n roll pub gigs under the name of Bus Pass. Much of the material was identical to that used in The Al Kirtley Three in the 1960s, but now, with an electronic keyboard, I could actually see the crowd, rather than having to stare at the front of an upright steam piano. I even persuaded my son, Pete, to sit in on drums for a couple of numbers, the first time we’d played together.

Much of the material was identical to that used in The Al Kirtley Three in the 1960s, but now, with an electronic keyboard, I could actually see the crowd, rather than having to stare at the front of an upright steam piano. I even persuaded my son, Pete, to sit in on drums for a couple of numbers, the first time we’d played together.

That was supplemented by a number of recording sessions,including a track on an album by The Tweenies and a 1991 single with the UK Mixmasters that actually got to number 14 in the charts, (and therefore earned yours truly a sizeable sum). I also did occasional gigs with a Swanage rock band, Cadillac, fronted by Martin Johnson, with Jake Jacobs on guitar, Geoff Welstead on tenor sax and Tom Marsh on bass, and with them I did the Swanage Carnival for several years, plus an extremely drunken tour of France with Johnny Hammond on drums. (See YouTube link). Jazz never went away entirely, however, and Mick Kirby and I continued to do the annual Jazz Day at my local pub, The Brickmakers Arms, in Windlesham, Surrey, (we did the first sixteen years of Jazz Days, from 1988 to 2003, and it carried on until 2018) working with a succession of other musicians, until the line-up settled down to what became Four Way Split, with Phil Berry on bass, and Terry McAvoy on guitar, and occasionally flute, plus, for a while, Trish Bassett on vocals. In later years we also augmented the line-up for the annual jazz day at The Brickmakers with Des James (who’s a dead ringer for Colin Powell) on congas. We did some great gigs together, including the National Theatre, and the London Weekend Television studios, and Four/Five Way Split is featured on several of the tracks on my two albums.

That was supplemented by a number of recording sessions,including a track on an album by The Tweenies and a 1991 single with the UK Mixmasters that actually got to number 14 in the charts, (and therefore earned yours truly a sizeable sum). I also did occasional gigs with a Swanage rock band, Cadillac, fronted by Martin Johnson, with Jake Jacobs on guitar, Geoff Welstead on tenor sax and Tom Marsh on bass, and with them I did the Swanage Carnival for several years, plus an extremely drunken tour of France with Johnny Hammond on drums. (See YouTube link). Jazz never went away entirely, however, and Mick Kirby and I continued to do the annual Jazz Day at my local pub, The Brickmakers Arms, in Windlesham, Surrey, (we did the first sixteen years of Jazz Days, from 1988 to 2003, and it carried on until 2018) working with a succession of other musicians, until the line-up settled down to what became Four Way Split, with Phil Berry on bass, and Terry McAvoy on guitar, and occasionally flute, plus, for a while, Trish Bassett on vocals. In later years we also augmented the line-up for the annual jazz day at The Brickmakers with Des James (who’s a dead ringer for Colin Powell) on congas. We did some great gigs together, including the National Theatre, and the London Weekend Television studios, and Four/Five Way Split is featured on several of the tracks on my two albums.

In 2004, after nearly 50 years, I decided to give up live gigs. My swansong was to be at the Bull’s Head in Barnes with Zoot Money. The line-up included Van Morrison’s guitarist, Ronnie Johnson, and even Bobby Tench came up to sing a few numbers. It was a great gig to go out on, and that was it for making music…

…or so I thought. One evening, early in 2010, Mick Kirby popped round with a box of old cassette tapes he’d found gathering dust in his garage. Mick had recorded these over the years at live gigs and at musical “soirees” at my house. Many of them had deteriorated but a few contained some half-decent bits of playing, and with a bit of persuasion from Mick, and he’s almost as good at persuasion as he is at playing drums, I agreed to use them as the basis for another album. The result was “and another thing…”, which was finally completed in late 2010, but not before I’d recorded 4 new tracks with Mick and Phil Berry, and even managed to lure Terry McAvoy up from the wild west of England to add a great guitar solo to Hill Street Blues. Even that wasn’t completely the end, as in January 2011 I plucked up courage to play twice in public, firstly with Zoot at the Bull’s Head in Barnes, then a few days later at my local pub for my good mate Kev’s birthday bash. You can see some snippets by scrolling up this page and clicking on the YouTube link on the right.

So what now? Who knows, maybe that’s finally it (this is beginning to sound like Hamlet dying), but there is talk of another gig coming up…

NB. There was. In addition to sitting in with Zoot Money a few more times over the past few years, I even did a full gig – well at least two sets, as there were a couple of support bands – when we put together Zoot Money’s Egg Roll Band again in June 2014 to raise funds for the Bournemouth Rock Tree. You can see a couple of pics at Gallery 2010s. And in October 2015 four of us from Tequila Sunrise did a gig at the wedding of Dave Crabtree’s daughter (see pic in Gallery 2010s).

And… in late 2017 I started gigging again, at first just occasionally, then from 2018 more regularly when I once more became part of Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, after a gap of nearly 57 years (Zoot called it furlough). I was lucky enough to be part of what turned out to be the final version of the Big Roll Band for six years, playing with some absolutely brilliant musicians until Zoot’s untimely death in 2024. He and I had been good mates for 66 years and I still miss all our daily laughs and insults, and I’ll forever be grateful that we had the chance to play regularly again for those last few years. There were some nice detailed obituaries in the national press, including a really nice tribute to him by Elton John in The Guardian, and a huge turnout for the funeral at Mortlake Crematorium, where Ronnie Johnson and I had the honour of giving two of the eulogies. When my wife recovers from her cancer treatment I’m hoping to organise a memorial gig for Zoot.Thanks for your patience, and don’t forget to check out the “What’s New? (and occasional blog)” page and the YouTube and MySpace links above. And if you want to take a look at a shameless piece of name-dropping please click here. And another thing…

Al Kirtley