Jerry Stooks, The Downstairs Club and the naming of Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band

As the Downstairs Club, Bournemouth (see Wikipedia page) was a focal point of my musical life in the early 1960s and (therefore?) had largely been forgotten, at least until I managed to get a blue plaque erected outside the site on 14 September 2014 (see Blue Plaque Unveiling page), I thought I’d add a few memories of it and of Jerry Stooks, who set it up. (NB. “anorak” only became a pejorative term many years after these events took place.)

As the Downstairs Club, Bournemouth (see Wikipedia page) was a focal point of my musical life in the early 1960s and (therefore?) had largely been forgotten, at least until I managed to get a blue plaque erected outside the site on 14 September 2014 (see Blue Plaque Unveiling page), I thought I’d add a few memories of it and of Jerry Stooks, who set it up. (NB. “anorak” only became a pejorative term many years after these events took place.)

.

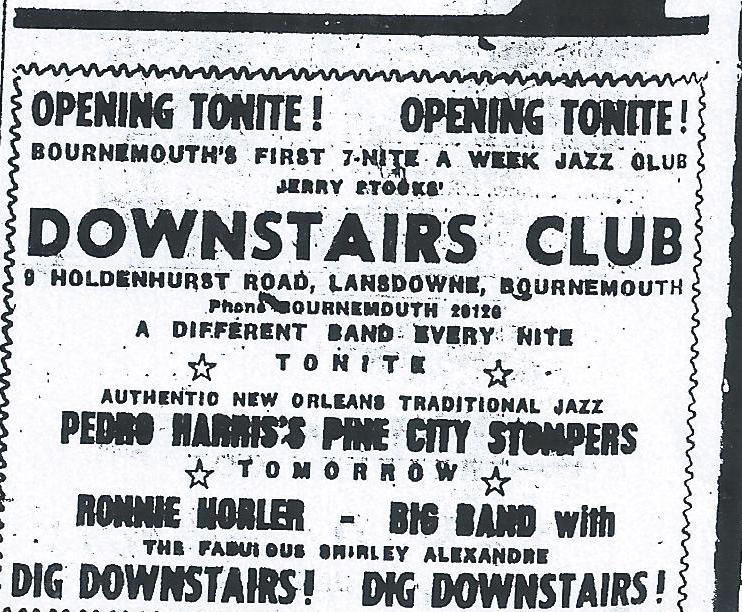

The Downstairs Club was opened by Jerry Stooks at 9 Holdenhurst Road, Lansdowne, Bournemouth on 3 May 1961. It occupied a cellar under a greengrocer’s shop and Jerry had also leased a narrow corridor leading from the street, together with two flats on the upper floors, one of which was occupied by Johnny Booker, better known as Johnny Martyn, (see link to obituary), a former member of The Vipers skiffle group. Johnny had a club foot and kept a pet monkey, (he was known as “Johnny de Monk” at the time), and neither of them seemed to venture outside, with predictable effects on the air quality in the flat. It stank.

The Downstairs Club was opened by Jerry Stooks at 9 Holdenhurst Road, Lansdowne, Bournemouth on 3 May 1961. It occupied a cellar under a greengrocer’s shop and Jerry had also leased a narrow corridor leading from the street, together with two flats on the upper floors, one of which was occupied by Johnny Booker, better known as Johnny Martyn, (see link to obituary), a former member of The Vipers skiffle group. Johnny had a club foot and kept a pet monkey, (he was known as “Johnny de Monk” at the time), and neither of them seemed to venture outside, with predictable effects on the air quality in the flat. It stank.

Jerry was a larger-than-life character, a tall, lanky jazz-loving upright-bass player, with a short, “beatnik-style” haircut, who drove a massive open-topped car of the type then so beloved by minor South American dictators. His parents were caretakers at the then privately-owned and extremely secretive Brownsea Island in Poole Harbour, where Jerry regularly stayed. His original aim was to establish the club as a full-time jazz venue, and this was reflected in his early booking policy. It soon became clear, however, that the real demand was for rock groups and shortly after the opening of the club, groups such as Zoot Money and the Blackhawks and Johnny King and the Raiders appeared there. Within a few weeks, fresh from our tour of the Midlands for Reg Calvert, Dave Anthony and the Ravers, soon to be the Rebels, followed suit, and we started working at the club on a regular basis.

Jerry continued to feature occasional jazz acts, and this was indirectly responsible for the naming of Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band. [ZM, if you’re reading this, I know you only remember the Chuck Berry bit, but my memory’s better than yours, coz it’s not full of notable experiences like yours is]. (NB. I’m indebted to the late Roger Collis for some of these prehistoric details.)

In October 1961 I was approached by Zoot and Rog Collis to join a new group they were putting together. Their original plan had been to include Kevin Drake, who was then playing clarinet with a trad band, on tenor sax and for Zoot to handle piano and vocals. However, Rog, an extremely tough and determined bandleader as well as a blistering guitarist, had decided that my piano technique was better than Zoot’s (if it had been organ I’d never have got the job) and he wanted Zoot to concentrate on vocals and on fronting the group. Rog had seen me with Dave Anthony at the Downstairs Club switching to the house piano for a few Fats Domino numbers, and I’d also played as a session pianist on a shellac recording by the Blackhawks of Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘Break Up’in 1960/61, so Rog wanted me in. (Adding a piano-player may have been purely for novelty value, along the lines of the dancing dog – the attraction lies not in the fact that it can dance well but that it can dance at all.) Mike “Monty” Montgomery on bass and Johnny Hammond on drums had already agreed to join and Kevin Drake could come on board later when his tenor sax technique had improved.

Just after the formation of the Big Roll Band Zoot and I gatecrashed a Johnny King & the Raiders gig at the Bure Club, Mudeford. Pic shows us doing Kansas City, and I still remember the opening bars of the guitar solo I played in it. How sad is that?

At first I wasn’t sure I wanted to leave Dave Anthony and the Rebels. The present line-up had only been in existence for a few months; I liked the guys and the band was successful with a slick professional sound. Thanks to Mike and Pete Giles’s connections we were getting work at the Bure Club, Mudeford and from the Howard Lock agency to replace the loss of gigs for Reg Calvert, and we’d retained our other venues. We were, however, still doing largely the same material I’d played with the Ravers for two years and a switch full-time from guitar to piano would mean a radical change for me. (It would also save me the cost of replacing my ageing Burns-Weill guitar). And the more I listened to Zoot’s musical ideas the more appealing the idea of a change became. Zoot felt that rock music had travelled too far from its rock’n’roll roots, and wanted to recreate the feel of black artists such as Ray Charles, Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

This is where it gets technical, folks, so non-musos may want to skip this bit. If you listen very carefully to, say, Johnny B. Goode by Chuck Berry, or even Good Golly, Miss Molly by Little Richard, you’ll find that the drummers, presumably because of their jazz backgrounds, are playing “ten-to-twos”, i.e. a swing beat, on the cymbal, against the hard-rock eight-to-the-bar of Chuck’s guitar or Little Richard’s piano. This sets up a tension between the instruments which produces more excitement and more of a loose “black” feel. That technique had largely disappeared by 1961. As Zoot put it one afternoon at a meeting with Rog Collis in my mother’s front room in Cowper Road, Moordown, “there’s too much rock and not enough roll” (a similar sentiment later applied to boogie-woogie by Chas & Dave in their 1981 single Poor Ol’ Mr. Woogie).

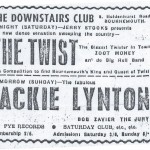

While Zoot was talking I was flipping through the local paper to see who was on at the Downstairs Club that night and saw it was jazz, featuring The Ronnie Horler Big Band. At the time I’d never heard of Ronnie Horler, but the term “band” sounded much cooler to me than “group” and I suggested that we ought to call ourselves a band, or, even better, “big band”, since we were adding piano and (as we thought at the time) tenor sax to the usual rock line-up of vocals, guitar, bass and drums. Zoot and Rog agreed instantly and Zoot put back on the record player my 78 rpm copy of Johnny B. Goode that we’d been playing earlier. “Listen to the third verse”, he said. “His momma told him some day you will be a man, and you will be the leader of a big roll band… that’s what we’ll call it: The Big Roll Band.”

Of course what Chuck actually sang was “big old band”, but my 78 record, which incidentally I’ve still got, was a bit crackly and we may perhaps be forgiven for the mistake. And maybe it wasn’t such a bad mistake at that. Zoot tells me that some years later he was talking to Chuck and told him the story outlined above. Chuck’s response was that he wished he’d thought of ‘big roll band’ when he was writing the lyrics!

Of course what Chuck actually sang was “big old band”, but my 78 record, which incidentally I’ve still got, was a bit crackly and we may perhaps be forgiven for the mistake. And maybe it wasn’t such a bad mistake at that. Zoot tells me that some years later he was talking to Chuck and told him the story outlined above. Chuck’s response was that he wished he’d thought of ‘big roll band’ when he was writing the lyrics!

In any event, after a few secret rehearsals (at one of which Hammond insisted on cooking baked beans on a primus stove next to his hi-hat), Zoot Money and the Big Roll Band was launched on an unsuspecting Bournemouth public on Sunday 12 November 1961 at the Downstairs Club. As far as I know, that was the first instance of any rock or pop group in the UK being referred to as a “band”.

Click here for the Bournemouth Echo ad for the first ever gig of Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band – my first piano playing gig. The previous night was my last gig as a lead guitarist, with Dave Anthony and the Rebels, also at the Downstairs Club.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Until our first gig Jerry Stooks wasn’t pleased. The formation of the Big Roll Band had resulted in several other bands breaking up, including Dave Anthony and the Rebels, one of Jerry’s major attractions, and he wasn’t convinced our very different style would catch on. Right from the start, however, the audiences loved the band and he didn’t take long to come round. We did, though, after a few months begin to attract some of the, shall we say, more liberally-fisted elements of the local population and the club started to get known for its regular punch-ups. We were, however, starting to pull in some prestigious gigs, culminating in a slot at the Royal Arcade Ballrooms in Boscombe, where, while the resident orchestra were on, Zoot insisted on standing behind their bandleader, Haydn Powell, and mimicking him with a lemonade straw for a baton, causing the brass section to lose their embouchure. Although the gig went down a storm, at the end of it Monty and Hammond announced that they were leaving, their places shortly being taken by Johnny King on bass and Pete Brooks on drums. The band had by this time decided to turn pro, and I left shortly afterwards, (little did I know that I’d rejoin the band more than 56 years later, in 2018), Kevin Drake at last coming in on tenor sax and Zoot taking over on keyboards. That became the 2nd line-up of the Big Roll Band and the first version to go pro, which is why it’s often mistakenly referred to as the “original” line-up.

The third version of Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band later went on to become a cult attraction on the London rhythm and blues scene, but that was several years after I’d refused to turn pro and left, though I remain friends with Zoot to this day, and with Rog until his untimely death in 2015. The history of the band after it left Bournemouth is well documented, but one by-product of its earlier years is always ignored. We introduced what was probably the first version of line-dancing in the UK.

The Hully Gully was a minor hit for The Olympics at the end of 1959, but the dance of the same name made no impact whatever in the jive-mad UK. The song had a nice feel about it, and Zoot added it to our list of numbers. During one of our first performances of it, Zoot began doing the dance steps of the “Southampton” jive – three steps to the side, and a gentle little kick – and the audience gradually followed suit, until they were all facing the stage in lines, mirroring his movements. We were now gigging across much of Southern England, and the dance quickly became a craze, though not always done to The Olympics’ song, as most conventional dance-bands hadn’t heard of it.

The Hully Gully was a minor hit for The Olympics at the end of 1959, but the dance of the same name made no impact whatever in the jive-mad UK. The song had a nice feel about it, and Zoot added it to our list of numbers. During one of our first performances of it, Zoot began doing the dance steps of the “Southampton” jive – three steps to the side, and a gentle little kick – and the audience gradually followed suit, until they were all facing the stage in lines, mirroring his movements. We were now gigging across much of Southern England, and the dance quickly became a craze, though not always done to The Olympics’ song, as most conventional dance-bands hadn’t heard of it.

We also clocked up another first: we were probably one of the first semi-pro rock’n’roll bands to join the Musicians’ Union. In the early 1960s, Bournemouth, as a major seaside resort, had the largest MU branch outside London, with all the major tourist attractions and the larger hotels featuring (unionised) live music. As our reputation grew it wasn’t long before the local MU branch officials started pestering us to join. At first we couldn’t see the point of parting with even a paltry amount of our band earnings in union subs, and anyway weren’t particular fans of the trade union movement, (after all, this was genteel Bournemouth). Eventually, however, Rog Collis relented and told us we were going to join. His motives were probably practical – if we wanted to graduate to the biggest Bournemouth venues we’d have to have union cards, and we probably felt flattered at this organisation of “grown-up” musicians almost begging us to join. Rog also probably had one eye on the band turning pro.

The decision having been made, we duly appeared before the local MU secretary, Pam Dobbin, and her executive committee, expecting to have our union cards bestowed upon us by a grateful union (I even had a modest acceptance speech ready). The reality was a little different, however. We were treated as humble petitioners and even had to endure a lecture on the history of the Tolpuddle Martyrs before they graciously permitted us to join. However we all managed to keep a straight face and left the meeting a few shillings poorer, but with our union cards safe in our pockets, and a feeling of slight superiority over all the other “amateur” (i.e. non-union) groups in the Bournemouth area. Although over the years I rarely had to produce my union card, I was called out on strike by the MU a few years later (see The Bournemouth Years – Piano) and remained a member of the union until the early 2000s.

The decision having been made, we duly appeared before the local MU secretary, Pam Dobbin, and her executive committee, expecting to have our union cards bestowed upon us by a grateful union (I even had a modest acceptance speech ready). The reality was a little different, however. We were treated as humble petitioners and even had to endure a lecture on the history of the Tolpuddle Martyrs before they graciously permitted us to join. However we all managed to keep a straight face and left the meeting a few shillings poorer, but with our union cards safe in our pockets, and a feeling of slight superiority over all the other “amateur” (i.e. non-union) groups in the Bournemouth area. Although over the years I rarely had to produce my union card, I was called out on strike by the MU a few years later (see The Bournemouth Years – Piano) and remained a member of the union until the early 2000s.

With the departure of the Big Roll Band to London in 1962 for its first abortive attempt at going pro (I’d joined the Sands Combo by then), the Downstairs Club gradually declined in popularity and Jerry decided to sell it and move on. My last memory of him at the club is of a largely empty room, with him playing double bass in a quartet with a contact mike stuck to the bottom of the bass. As there was no working house mike, he had to make his announcements by lying flat on his back and speaking up into the instrument.

After Jerry left, the club carried on under different names – The Lansdown (sic) Beat Club,  the hugely successful Le Disque a Go! Go!, etc. and ironically it was during this period that jazz was reintroduced at the club with a Saturday late night session starting at midnight, at which I played regularly with the Crispin Street Quintet and later the Lennie Lee Quintet. It probably went through a few more name changes after then, before becoming Glasshoppers, which my daughter Emma frequented, (perhaps a little too often?) in the late 1980s while she was at Bournemouth University. (By then the club had doubled in size and occupied the cellars under nos. 7 and 9 Holdenhurst Road.)

the hugely successful Le Disque a Go! Go!, etc. and ironically it was during this period that jazz was reintroduced at the club with a Saturday late night session starting at midnight, at which I played regularly with the Crispin Street Quintet and later the Lennie Lee Quintet. It probably went through a few more name changes after then, before becoming Glasshoppers, which my daughter Emma frequented, (perhaps a little too often?) in the late 1980s while she was at Bournemouth University. (By then the club had doubled in size and occupied the cellars under nos. 7 and 9 Holdenhurst Road.)

On Sunday 14 September 2014 a blue plaque outside the club was unveiled by Zoot Money. For a pictorial record of the occasion plus links to a video of the speeches and unveiling and press articles please click here.

On Sunday 14 September 2014 a blue plaque outside the club was unveiled by Zoot Money. For a pictorial record of the occasion plus links to a video of the speeches and unveiling and press articles please click here.

.

.

Jerry Stooks later switched from double-bass to drums, and carried on playing for many years. I believe he opened a shop, and in 1983 he stood as a general election candidate for the Official Loony Monster Green Chicken Party. I’m ashamed to say that I still have his vinyl copy of The Atomic Mr. Basie album and feel a pang of guilt every time I see the equation e=mc2.

Newsflash! The guilt has now been assuaged, albeit some years after Jerry passed away. On 17 July 2015 I finally returned the album to Jerry’s son, Dan Stooks, 53 years after I borrowed it.As is well known, Zoot Money and the Big Roll Band went on to become a major part of the British rhythm and blues scene, reaching the Top Thirty singles charts in 1966 with “Big Time Operator”. For some years Zoot also combined music with acting. Though too modest to say so, he is thought to be the only person ever to have taken a phone call from Paul McCartney while in prison. (He was filming the movie of “Porridge” with Ronnie Barker on location in Chelmsford Prison in 1979 when one of the warders asked him “is your name Money? There’s some bloke called McCartney on the phone for you”. The result was the 1980 album “Mr. Money”, issued on Paul McCartney’s MPL label.)

Don’t forget to check out the page on the unveiling of the Blue Plaque at the site of the old Downstairs Club by clicking here. And for a review I wrote of a 2003 Guildford concert of the British Legends of Rhythm and Blues UK Tour featuring Zoot Money please click here.

Okay, that’s enough of that; on, on and ever onwards to The Bournemouth Years – Piano.