The Bournemouth Years (Piano)

The Sands Combo (L-R Al Kirtley, Graham Douglas, Roger Bone, Pat “Peewee” Shehan)

In 1962 I left the Big Roll Band when it moved to London for its first abortive attempt at going pro and immediately joined the Sands Combo.

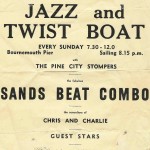

Though not as bluesy in its material as the Big Roll Band, the Sands had a wider repertoire of pop music, including the new craze of The Twist, and we soon secured a residency at the weekly “Big Beat” session at The Pavilion, a vast building in the centre of Bournemouth, and probably one of the most prestigious venues on the south coast. Vocals were handled by Dave Anthony, later supplemented by Zoot Money, temporarily back in Bournemouth. The vocalist with the support band was Tony Blackburn, later to find fame as a disc-jockey, whom Zoot insisted on announcing as “Tony Blackhead and the Pimples”. For the early part of Dave Anthony’s first set Zoot had to play piano while I was en route from my book-keeping class for the Institute of Bankers exams, on my arrival sliding off the piano stool as I slid on the other end, hopefully without a chord being missed.

Whilst with The Sands I acquired my first “synthesiser”, a Selmer Clavioline, a small analogue keyboard, then way ahead of its time. The technology was primitive by today’s standards: it was monophonic (i.e. could only play one note at a time) and if, like me, you couldn’t afford the stand, it had to be fixed to the right underside of the piano by a couple of screw-in brackets, which didn’t go down very well with the owners of the house pianos. You controlled the volume by a lever moved sideways with your right knee. However, it meant that I could replicate the solo in Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and the melody of “Telstar” by The Tornados, both of which were done on the clavioline. Though many years later I went through the usual range of digital synths used by most keyboard players (Wasp, Juno 6 & 60, DX7, Korg M1, etc), as well as a range of pianos (inc a Fender Rhodes Stage 73 and a series of Yamahas from the PF15 to the P-200, a Technics P50, and now my lovely Nord Piano5, I still have fond memories of that little clavioline, not least because it was the first time since giving up the guitar that I could be the loudest player in the band. (Q. How do you get a rock guitarist to turn down? A. Put some dots in front of him. Q. How do you get him to turn off? A. Ask him to play them.)

Whilst with The Sands I acquired my first “synthesiser”, a Selmer Clavioline, a small analogue keyboard, then way ahead of its time. The technology was primitive by today’s standards: it was monophonic (i.e. could only play one note at a time) and if, like me, you couldn’t afford the stand, it had to be fixed to the right underside of the piano by a couple of screw-in brackets, which didn’t go down very well with the owners of the house pianos. You controlled the volume by a lever moved sideways with your right knee. However, it meant that I could replicate the solo in Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and the melody of “Telstar” by The Tornados, both of which were done on the clavioline. Though many years later I went through the usual range of digital synths used by most keyboard players (Wasp, Juno 6 & 60, DX7, Korg M1, etc), as well as a range of pianos (inc a Fender Rhodes Stage 73 and a series of Yamahas from the PF15 to the P-200, a Technics P50, and now my lovely Nord Piano5, I still have fond memories of that little clavioline, not least because it was the first time since giving up the guitar that I could be the loudest player in the band. (Q. How do you get a rock guitarist to turn down? A. Put some dots in front of him. Q. How do you get him to turn off? A. Ask him to play them.)

Our residency at The Pavilion brought us within the orbit of the Bournemouth musical “mafia” that ran most of the main tourist attractions, and several other prestige gigs came our way, including a weekly gig on the “Jazz and Twist Boat”, sailing from Bournemouth to Swanage, about fifteen miles down the coast. The ship was the “Embassy”, a paddle steamer that was already well past middle age when it took part in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation, but on a calm, clear night, the trip was idyllic. We began to regard ourselves as seasoned matelots, until one night, hove to in Poole Bay in the midst of a Force 8, because the captain wouldn’t risk rounding the Old Harry Rocks, I found myself aiming for Middle C, and hitting B flat above, untypical even of my limited technique. Fortunately, the embarrassment this caused was truncated when I threw up over an onboard poster, describing “A Starlight cruise for young and old along the spectacular Dorset coastline with continuous Bar and Buffet”. It was the only bout of seasickness I’ve ever had, but I wasn’t alone, and the Sands Combo, which had started the gig as a six-piece, ended up as a trio. Cruise holidays have never appealed to me since.

Our residency at The Pavilion brought us within the orbit of the Bournemouth musical “mafia” that ran most of the main tourist attractions, and several other prestige gigs came our way, including a weekly gig on the “Jazz and Twist Boat”, sailing from Bournemouth to Swanage, about fifteen miles down the coast. The ship was the “Embassy”, a paddle steamer that was already well past middle age when it took part in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation, but on a calm, clear night, the trip was idyllic. We began to regard ourselves as seasoned matelots, until one night, hove to in Poole Bay in the midst of a Force 8, because the captain wouldn’t risk rounding the Old Harry Rocks, I found myself aiming for Middle C, and hitting B flat above, untypical even of my limited technique. Fortunately, the embarrassment this caused was truncated when I threw up over an onboard poster, describing “A Starlight cruise for young and old along the spectacular Dorset coastline with continuous Bar and Buffet”. It was the only bout of seasickness I’ve ever had, but I wasn’t alone, and the Sands Combo, which had started the gig as a six-piece, ended up as a trio. Cruise holidays have never appealed to me since.

The Sands Combo line-up broke up shortly afterwards, due to a dispute over pay, and I teamed up with a fellow ex-Sands member, Nigel Street, an accomplished saxophonist, who had started a modern jazz group. I’d wanted to play jazz for several years, but never considered my technique to be up to it, but, with a bit of encouragement from Nigel, I joined what eventually became the Crispin Street Quintet, featuring Nigel and me, Jimmy and Francis Shipstone on guitar and bass respectively, and Tom Costello on drums. Due to a combination of my lousy technique, and the fact that most of the house pianos at our gigs didn’t work properly in the upper register, my solos didn’t exactly dominate the band, but I could lay down a half decent accompaniment, and even managed to arrange a couple of numbers. I also learned a fair selection of jazz standards, which was to stand me well a couple of decades later.

The Sands Combo line-up broke up shortly afterwards, due to a dispute over pay, and I teamed up with a fellow ex-Sands member, Nigel Street, an accomplished saxophonist, who had started a modern jazz group. I’d wanted to play jazz for several years, but never considered my technique to be up to it, but, with a bit of encouragement from Nigel, I joined what eventually became the Crispin Street Quintet, featuring Nigel and me, Jimmy and Francis Shipstone on guitar and bass respectively, and Tom Costello on drums. Due to a combination of my lousy technique, and the fact that most of the house pianos at our gigs didn’t work properly in the upper register, my solos didn’t exactly dominate the band, but I could lay down a half decent accompaniment, and even managed to arrange a couple of numbers. I also learned a fair selection of jazz standards, which was to stand me well a couple of decades later.

By the end of 1963, Jimmy and Francis Shipstone had decided to turn pro and work abroad, and, true to form, I left, and played for a short time with the Lennie Lee Quintet. (Jimmy and Francis’s group later evolved into The Nite People, which became a cult R’n’B band). It was not long, however, before a local agent, Vic Allen, approached me to join a new group that was being put together by a local businessman, Roy Simon, who evidently saw himself as the next Brian Epstein. Mike and Pete Giles, with whom I’d played in Dave Anthony and the Rebels, had already agreed to join. Though a clothing manufacturer by profession, Roy apparently had extensive show-business connections, and had “been in the Navy with David Jacobs”. It only occurred to us later how large the Royal Navy was in World War II.

By the end of 1963, Jimmy and Francis Shipstone had decided to turn pro and work abroad, and, true to form, I left, and played for a short time with the Lennie Lee Quintet. (Jimmy and Francis’s group later evolved into The Nite People, which became a cult R’n’B band). It was not long, however, before a local agent, Vic Allen, approached me to join a new group that was being put together by a local businessman, Roy Simon, who evidently saw himself as the next Brian Epstein. Mike and Pete Giles, with whom I’d played in Dave Anthony and the Rebels, had already agreed to join. Though a clothing manufacturer by profession, Roy apparently had extensive show-business connections, and had “been in the Navy with David Jacobs”. It only occurred to us later how large the Royal Navy was in World War II.

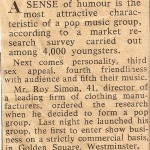

Roy believed that the “Merseybeat” sound was a temporary aberration, and, as a lover of traditional jazz and big bands, decided to include a trombone in the lineup, to give the band “wider appeal”. He had apparently carried out extensive market research into what the teenage girl record-buying public wanted, (it later transpired that he’d asked his teenage daughter and her friend, who must have been trombone-freaks), and had discovered that the key characteristics were 1,Good looking. 2,Very tall. 3, Dark. 4, Very thin – “the lean and hungry look” (Roy had read Julius Caesar at school) 5, Personality. 6, Good musicians. We certainly qualified under item 4, and possibly 6 (Phil Collins later declared Mike Giles to be his favourite drummer). Item 2 was, however, a problem, since the trombonist, Mike Blakesley was only marginally taller than his instrument when the slide was fully extended. Undaunted, Roy doctored the market research to the effect that 26% of the “respondents” – believed to be vertically-challenged girls – did not want their heroes too tall.

Roy believed that the “Merseybeat” sound was a temporary aberration, and, as a lover of traditional jazz and big bands, decided to include a trombone in the lineup, to give the band “wider appeal”. He had apparently carried out extensive market research into what the teenage girl record-buying public wanted, (it later transpired that he’d asked his teenage daughter and her friend, who must have been trombone-freaks), and had discovered that the key characteristics were 1,Good looking. 2,Very tall. 3, Dark. 4, Very thin – “the lean and hungry look” (Roy had read Julius Caesar at school) 5, Personality. 6, Good musicians. We certainly qualified under item 4, and possibly 6 (Phil Collins later declared Mike Giles to be his favourite drummer). Item 2 was, however, a problem, since the trombonist, Mike Blakesley was only marginally taller than his instrument when the slide was fully extended. Undaunted, Roy doctored the market research to the effect that 26% of the “respondents” – believed to be vertically-challenged girls – did not want their heroes too tall.

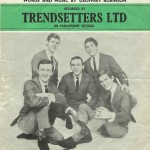

Roy’s original intention had been to name the band simply “The Trendsetters”, but he had set up a separate company under the name of “Trendsetters Ltd.”, presumably to ring-fence the music operations from his other commercial interests. He decided that one of the band members should be named as a director and due to my day job with a clearing bank he appointed me as a director, though understandably with an allocation of only one (non-voting) share out of 100. I was, however, issued with a Trendsetters Ltd. business card showing my name as a director, which of course I flaunted shamelessly to my colleagues in the bank.

Roy’s original intention had been to name the band simply “The Trendsetters”, but he had set up a separate company under the name of “Trendsetters Ltd.”, presumably to ring-fence the music operations from his other commercial interests. He decided that one of the band members should be named as a director and due to my day job with a clearing bank he appointed me as a director, though understandably with an allocation of only one (non-voting) share out of 100. I was, however, issued with a Trendsetters Ltd. business card showing my name as a director, which of course I flaunted shamelessly to my colleagues in the bank.

After an avalanche of publicity, including a spot alongside Henry Mancini on Southern Television’s “Three Go Round”, and subsequently four of our own fifteen minute shows on Radio Luxembourg, our first single, “In a Big Way” (play track on YouTube), was released on 26 March 1964. (The writer of the song, Geoff Robinson, had originally been intended to be part of the band, but decided against it and was replaced by Bruce Turner on guitar and lead vocals.) For many years, I laboured under the illusion that “In a Big Way” had made the lower, and therefore unpublished, reaches of the charts, but sadly the Guinness Book of Hit Singles doesn’t show it having reached the top seventy-five, even for one week. (Amazingly, the two Trendsetters singles later became collectors items. As at September 2003, In a Big Way was priced at $43.95 and Move on Over at £15. And, even more surprisingly, in 2013 Move on Over was digitally remastered and included as track 35 on an Italian album, Ballroom Beat, Vol. 2.

After an avalanche of publicity, including a spot alongside Henry Mancini on Southern Television’s “Three Go Round”, and subsequently four of our own fifteen minute shows on Radio Luxembourg, our first single, “In a Big Way” (play track on YouTube), was released on 26 March 1964. (The writer of the song, Geoff Robinson, had originally been intended to be part of the band, but decided against it and was replaced by Bruce Turner on guitar and lead vocals.) For many years, I laboured under the illusion that “In a Big Way” had made the lower, and therefore unpublished, reaches of the charts, but sadly the Guinness Book of Hit Singles doesn’t show it having reached the top seventy-five, even for one week. (Amazingly, the two Trendsetters singles later became collectors items. As at September 2003, In a Big Way was priced at $43.95 and Move on Over at £15. And, even more surprisingly, in 2013 Move on Over was digitally remastered and included as track 35 on an Italian album, Ballroom Beat, Vol. 2.

Programme from New Theatre, Oxford 28 March 1964. Presumably Trendsetters Ltd. qualified as the ‘supporting company’.

Trendsetters Limited carried on for a few years, before evolving, via “The Trend”, into Giles, Giles and Fripp, and finally King Crimson, but, of course, I’d left long before then, although I do play on one of the tracks on The Brondesbury Tapes by Giles, Giles and Fripp, recorded in 1967 and released in 2001, plus several tracks with The Trend recorded at Abbey Road studios and released in 2009 as part of “The Giles Brothers 1962-1967” CD. (Peter Giles generously refers to me in the sleeve notes of The Brondesbury Tapes as “a great piano player who steadfastly refused to turn pro”.) My place in Trendsetters Limited was taken by Allan Azern, a great pianist, and because we’re both called “Al” or “Allan” the two of us are often mixed up in the occasional articles which are still written about the group.

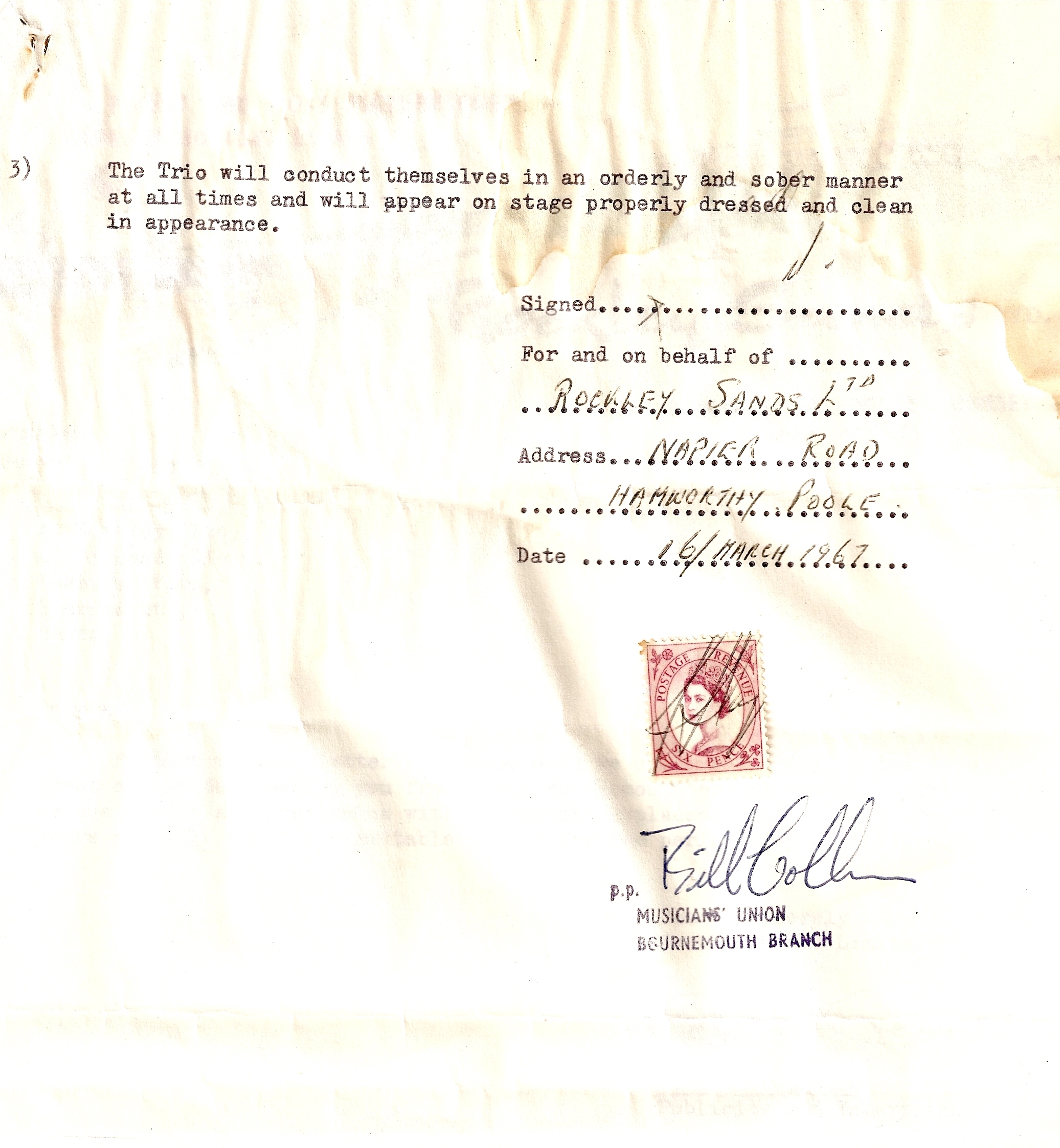

I’d stayed close friends with the original bass player of the Big Roll Band, Mike “Monty” Montgomery, and we decided to put together a trio, with Roger de Souza on drums, playing a wide range of material, from waltzes and quicksteps to rock’n’roll and pop. Monty and I handled the vocals jointly, the theory being that each of our voices would cancel out the imperfections in the other’s – a nice theory, except that Monty sang sharp, and I was usually flat. After a shaky start, with  me trying to solo frantically through quicksteps as if I were Teddy Wilson (it probably sounded more like Harold Wilson), we gradually improved, and the gigs started rolling in. A steady stream of functions, (our fees for which were always in guineas and not pounds, as the extra shilling in the pound paid for our petrol), supplemented a series of residencies, including a lengthy one at the Durlston Court Hotel, the former home of the comedian Tony Hancock, and a long-running stint, under the name of The Rockefellers, at Rockley Sands holiday camp, where we were called out on strike by the Musicians’ Union, due to our combined wages being ten shillings short of the MU rate. The dispute lasted ten minutes before the management caved in.

me trying to solo frantically through quicksteps as if I were Teddy Wilson (it probably sounded more like Harold Wilson), we gradually improved, and the gigs started rolling in. A steady stream of functions, (our fees for which were always in guineas and not pounds, as the extra shilling in the pound paid for our petrol), supplemented a series of residencies, including a lengthy one at the Durlston Court Hotel, the former home of the comedian Tony Hancock, and a long-running stint, under the name of The Rockefellers, at Rockley Sands holiday camp, where we were called out on strike by the Musicians’ Union, due to our combined wages being ten shillings short of the MU rate. The dispute lasted ten minutes before the management caved in.

The trio was known simply as “The Al Kirtley Three”, and by the late 1960s, Johnny Hammond, who’d also been in the Big Roll Band, took over on drums from Roger de Souza. The functions and residencies continued, including two nights a week at the Potters Arms in Hamworthy. That was an all-out rock’n’roll gig, (with no guitarist), therefore involving a lot of eight-to-the-bar chords in the right hand, coupled with Jerry Lee Lewis glissandos, and all done on a beaten-up old upright piano. I soon found that by the second set my right hand was bleeding all over the keys, making them slippery, and although I didn’t feel any pain, thanks to the number of pints we sank every night, it was becoming a nuisance. I managed to solve the problem by steeping my fingers in a saucer of surgical spirit before leaving for the gig, thus making them rock-hard, and able to withstand a night’s pounding at the keys.

The trio was known simply as “The Al Kirtley Three”, and by the late 1960s, Johnny Hammond, who’d also been in the Big Roll Band, took over on drums from Roger de Souza. The functions and residencies continued, including two nights a week at the Potters Arms in Hamworthy. That was an all-out rock’n’roll gig, (with no guitarist), therefore involving a lot of eight-to-the-bar chords in the right hand, coupled with Jerry Lee Lewis glissandos, and all done on a beaten-up old upright piano. I soon found that by the second set my right hand was bleeding all over the keys, making them slippery, and although I didn’t feel any pain, thanks to the number of pints we sank every night, it was becoming a nuisance. I managed to solve the problem by steeping my fingers in a saucer of surgical spirit before leaving for the gig, thus making them rock-hard, and able to withstand a night’s pounding at the keys.

As usual, we had a load of laughs, and during Hammond’s regular drum solo in “Ready Teddy”, Monty and I would squirt him with soda siphons, until the landlord complained at the cost of the soda. For a while this became such a popular and fashionable residency that the landlord had to lock the doors to prevent more people from trying to get in, which of course only added to its “cult” appeal. Of course, being rock’n’roll, after a while the inevitable punch-ups began, but, as on RMS Titanic, the band played on, (though in our case we survived unscathed).

until the landlord complained at the cost of the soda. For a while this became such a popular and fashionable residency that the landlord had to lock the doors to prevent more people from trying to get in, which of course only added to its “cult” appeal. Of course, being rock’n’roll, after a while the inevitable punch-ups began, but, as on RMS Titanic, the band played on, (though in our case we survived unscathed).

This line-up continued until I moved away from Bournemouth in November 1970, and gave up playing for seven years.

(Incidentally, Monty’s niece, Janet Montgomery, is now a well-known film and TV actress – see Wikipedia article.)

Congratulations. You’ve probably made it further than both previous readers of these meanderings. To qualify for your gold star, though, you need to get through what is mercifully a short coda covering…